“It’s of some interest that the lively arts of the millennial U.S.A. treat anhedonia and internal emptiness as hip and cool. It’s maybe the vestiges of the Romantic glorification of Weltschmerz, which means world-weariness or hip ennui. […] Forget so-called peer-pressure. It’s more like peer-hunger. No? We enter a spiritual puberty where we snap to the fact that the great transcendent horror is loneliness, excluded encagement in the self. Once we’ve hit this age, we will now give or take anything, wear any mask, to fit, be part-of, not be Alone, we young. The U.S. arts are our guide to inclusion. A how-to. We are shown how to fashion masks of ennui and jaded irony at a young age where the face is fictile enough to assume the shape of whatever it wears. And then it’s stuck there, the weary cynicism that saves us from gooey sentiment and unsophisticated naiveté. Sentiment equals naiveté on this continent.” (Wallace 2007: 694)

David Foster Wallace was a writer who has been heralded throughout the ever scrolling pages of Tumblr as a lone voice of sincerity and empathy in a world corrupted by inauthentic ironists. Ironists whose cynical stance towards the world serves as the barrier to meaningful human connection. This is one of the downsides to popularity; it can result in the nuances of your work being lost in the congealing cloud of public opinion. Wallace was indeed a critic of irony and cynicism, but these were also some of his most effective tools for both storytelling and commentary. Frequently, his lamentation about the limits to irony in particular are confused for an outright rejection of this mode of engagement with the world.

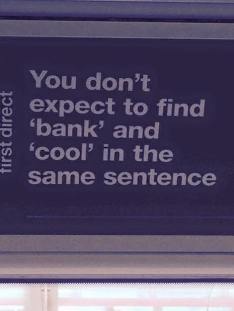

To summarize Wallace’s critique of irony, much of which is found overtly stated in his essay E Unibus Plurum, we could say that during the heights of that strangely placid decade for the West, the 90s, postmodernism appeared already stuck. The apparent death of the metanarratives (incorrectly attributed to Lyotard, who cited a mere incredulity in our relationship to them), left us groping for meaning in a world that had continued on after the “end of history”. Even Fukuyama, who coined the term, seemed melancholic at the prospect of having little more than new product releases and branding strategies in our future. The postmodern ironic stance, which had help bring this world into being by allowing us to stand outside the grand narratives of communism, conservatism, capitalism and religion, had been defanged, as all but one of these narratives had gone on to lose their power. As Wallace remarked on Charlie Rose “Burger King now sell hamburgers with ‘You gotta break the rules’”. Consumer capitalism had won the day, ushering us towards a boring dystopia.

Capitalist realism is a term that can help us to view our present as a historical period. Fisher took as the defining moment for this period Margaret Thatcher’s enunciation that “there is no alternative” to what is now called neoliberal capitalism for social organisation.

Unlike his literary hero Don Delillo, Wallace does not have much in the way of a developed theory of capitalism, at least not in Infinite Jest, the peak of his supposedly anti-ironic period. Or to put this more precisely, his theory of capitalism is one of antagonism with soviet communism.hat Wallace is lacking, perhaps purely because of his historical vantage point, is the ability to connect his concern about reality to the perspective of, what Mark Fisher would term, Capitalist Realism.

Capitalist realism is a term that can help us to view our present as a historical period. Fisher took as the defining moment for this period Margaret Thatcher’s enunciation that “there is no alternative” to what is now called neoliberal capitalism for social organisation. He argued that this has produced a discourse so powerful that, for many, it has foreclosed the possibility that there could be anything outside of capitalism. However, identifying this is the first step to escaping this logic and being able to imagine a world organised differently. The difficulty is that, for Wallace, recognising his present as capitalist realism would have required the capacity to fully objectify his present.

I would argue that this is a missing piece in Infinite Jest 1, which has formed Wallace’s understanding of irony. For Wallace, irony take you outside of a metanarrative, allowing you to see the absurdities of a narrative from a position unbound by its particular value systems. But when faced with the historical situation wherein most of these competing narratives appeared to have collapsed, where consumer capitalism is the only narrative that remains, irony cannot help but be fully incorporated as that single remaining narrative. In the absence of competition, the narrative of consumer capitalism begins to appear as if it were reality. It is difficult to see the characteristics of the present in which you find yourself because the now is slippery and resistant to objectification. That said, despite the fact that Wallace seems unable to fully objectify his time, by looking to the future within the novel he did produce a prescient picture of our present within Capitalist Realism. (Apart from the stuff about entertainment cartridges but I think that was joke).

The reason to focus on this is that we need to make clear a distinction, which is often fudged in readings of what constitutes postmodernism. That distinction being, that metanarratives are not the same material they structure. They help construct our relationships with that material but are not the same as that material. Socialism is a way to think about the social field that conceives it, conservatism is a way to structure a desire for stability and homogeneity. These are discursive frames that cannot fully contain the thing that they describe. Nowhere is this more clear than capitalism. Basically, all capital is a resource from which more resources can be produced. If you buy some wood and tools these could be considered capital, because if you turn them into some chairs you might be able to sell them for more than the cost of the resources and then buy even more. That is the phenomenon capitalism has narrativized, to make the claim that allowing individuals to pursue capital for themselves will produce the greatest social good, however that is defined. Regardless of whether this formulation is true, whenever possible the mechanism of capital itself will take place if it is allowed to.

This is what makes capitalism different from the other metanarratives. Its object requires very little from discourse to function. For socialism or conservatism, the objects these narratives address emerge almost entirely from discourse (though this is distinct from the discourse that appends an -ism to them). Socialism requires people to agree upon a social field, conservatism requires there to be an agreement about morality. From the postmodern ironist perspective, both of these metanarratives are vulnerable as the object is tied too closely to the narrative. Whereas for capitalism, while discourse can affect a particular price of a particular thing, the concept of capital remains outside discourse. (For a more thorough and much denser explanation of this, I’d recommend the work Maurizzio Lazzarato on a-signifying semiotics). The upshot of this is that capitalism has its own way of incorporating irony into its discourse, as cynicism.

In the novel, as a point of critique but also optimism, Wallace suggests to us that cynicism and naivety are not mutually exclusive.

Wallace has a habit of using the terms irony and cynicism interchangeably when critiquing the postmodern condition after the end of history. However, theorist Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi argues that such a conflation is a mistake and the distinction between these terms is vital to overcoming our present predicament. He writes;

“The common starting point is that both the ironist and the cynic suspend belief in the moral content of truth (and also in the true content of morality). They know that the True and the Good do not exist in God’s mind, nor in history, and they know that human behaviour is not based on respect for any law, but on empathy and shared pleasure […]. The cynical person bends to the law while mocking its values as false and hypocritical, while the ironic person escapes the law and creates a linguistic space where the law has no effectiveness. The cynic is someone who wants to be on the side of power but does not believe in its righteousness. The ironist simply refuses the game, and recreates the word as an effect of a linguistic enunciation.” (Berardi 2012: 20)

With this, we can perhaps cast cynicism as a defanged irony. This is a mode of behaviour that only appears ironic from within the conditions of capitalist realism, thus it never steps outside the metanarrative discourse and has not actually “refused the game”. Perhaps, if we engage with an objectification of our present systems of society and power as capitalist realism, we can produce an outside into which to step and thus begin to re-fang irony. Still, the problems of capital may persist, but this may at least allow us to “refuse the game” of capitalism. Though we may be left to ask, what would such re-fanged irony would look like? At the risk of making this all the more complicated, I would suggest that Wallace, in Infinite Jest, was onto something that could help us. I would suggest we consider irony, or the irony we need, to be the result of a collision between cynicism and naivety.

In the novel, as a point of critique but also optimism, Wallace suggests to us that cynicism and naivety are not mutually exclusive. According to the literary scholar Marshall Boswell, this is the defining characteristic of most of Wallace’s work. And in Infinite Jest, this lack of contradiction is demonstrated in ways that are often heartbreaking. A particularly poignant example of this is the story of the abuse victim, reformed burglar, recovering addict and arguably the emotional center of the novel, Don Gately. With Gately, we see an unresolvable contradiction in the ways in which he engages with the rituals of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) that have helped him so much. In particular the task of relinquishing his will to that of a higher power. Gately does not believe in any sort of god, in fact, he finds the notion ridiculous, but every day he is one his knees next to his bed asking the ceiling to relieve him of his will. This is a moment of knowing and cynical surrender to the naive belief that this quasi-mystical system will allow him to escape his addiction. Ironically, for Gately, it seems to be working.

Contrary to the claims of Wallace’s fans on Tumblr, this is the very definition of postmodern irony at work. As mentioned above, people often refer to Lyotard’s definition of the postmodern condition as if it enunciated the reality of a crass relativistic nihilism by ending the metanarratives, Wallace included. Again, we can see the problem of popularity at play. What Lyotard actually claimed was that the postmodern condition could be characterized as an “incredulity towards metanarratives”. This, I would argue, is exactly the position of Berardi’s ironist or Gately on his knees in Infinite Jest; a position of incredulity or an inability to believe fully. This disbelief does not automatically destroy the conception of reality a narrative puts forth, rather it simply lets one step outside a narratives confines so as we can better appraise its use. To consider irony a defanged tool of consumer capitalism is buy into fully to the metanarrative of capitalist realism. Instead, we need to re-fang ironic incredulity if we are ever to escape our boring dystopia.

- For those who don’t know, Infinite Jest is Wallace’s magnum opus, a thousand page epic set in near-future, late capitalist dystopia in which addiction, entertainment and loneliness have metastasized. It also features over 300 endnotes. ↩